Fourteen years before, man had first split the atom at the University of Chicago. That was a World War II government project. The atomic bomb had followed.

But the war was long over. Federal authorities had finally given

the green light to American business. Atomic energy would now be

harnessed for peaceful purposes.

The new reactor was located at the Illinois Institute of Technology--specifically, the Armour Research Foundation. Twenty-four industrial firms had joined IIT to fund the $750,000 program. The reactor was nicknamed "the atomic furnace."

The 1942 atom-split had been shrouded in wartime secrecy. This morning's event was open to the public. The Armour building was packed with reporters as director Haldon Leedy described what was going to happen.

Leedy said there was no danger operating a nuclear reactor in the middle of a crowded city. The furnace itself was made of concrete five feet thick, and numerous other safeguards were in place. Lab workers and the people of Chicago would be shielded from any radioactive leak.

As an added bonus, the reactor would not pollute the air. "No fumes, gasses, smoke, or other materials will be exhausted," Leedy explained. All those noxious byproducts would be blocked by a special containment system.

Atomic energy had many possible uses. Nuclear power was a cheap, endless source of fuel. New plastics and other synthetics would be developed. Radiation could be used to sterilize food, to destroy disease molds--perhaps even in the fight against cancer.

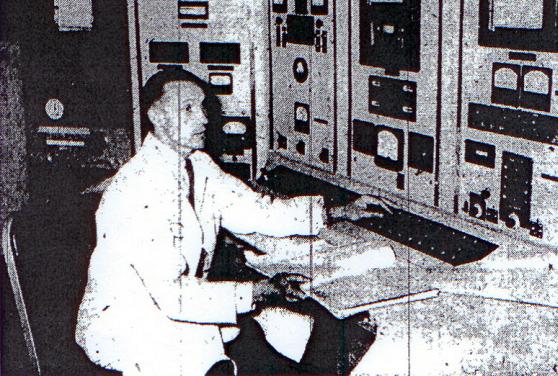

The briefing concluded. At 11:15 Dr. Martin Remley sat down at a control console outside the reactor room. He began flicking switches.

On the other side of a plate glass window, behind two airlock doors, the atom furnace began humming. An alarm bell clanged. Overhead, a signal light flashed the words "REACTOR ON."

The IIT atom furnace was a vision of the future. Atomic energy for commercial use was here to stay. And though critics continue to point out safety concerns, it's difficult to imagine a world without nuclear power.

UNKNOWN CHICAGO SOURCE: Chicago Tribune, June 29, 1956, section 4:7.